Article Contents

The Quick Guide to Forming a Subchapter Corporation (S Corp)

One of the more important, yet sometimes overlooked, aspects of succeeding with your small-business is figuring out how to choose the structure that works best for you. The business structure you want determines how much tax you will pay, how much liability you have, and even where you can do business. Sole proprietorships require very little paperwork to start and provide the advantages of “pass-through” taxation. However, these entities do not safeguard owners from liability. Traditional corporations provide liability protection. C corps subject their owners to “double taxation,” both on the company’s profits and on individual shareholder’s distributions from the company. Even before the formation of what is now a common hybrid business structure, the limited liability corporation (LLC), the United States wanted to create a way for small-business owners to have both liability protection and avoid double taxation. The subchapter or small-business corporation, commonly referred to as the S corp, accomplishes both.

What is a subchapter or small business corporation (S Corp)?

The S corp is a change of the tax code that Congress enacted into law in 1958, primarily to give a competitive leg up to small businesses. Politicians on both sides of the aisle had concerns about the consolidation of too much power in the hands of large, multinational corporations; with big business, big labor, and big government controlling the reins of American industry among them, the fear was that there would no longer be any room for private enterprise. The creation of the S corp was an economic boon to small-business owners, who at the time paid much higher tax rates than Americans do today. In 1958, the top corporate tax rate was 52 percent, and the top individual tax rate was 91 percent. The IRS would tax dividends paid to a high-income shareholder at a rate of 96 percent, and even a shareholder with a median-family income would be subject to a tax rate of 60 percent. S corps got rid of the double taxation and crippling tax burden, providing an incentive for individuals to invest the savings directly into their own small and family businesses. The tradeoff for avoiding high taxation were some restrictions on how S corps could structure themselves. These restrictions are as follows:

- S corps cannot have more than 100 shareholders.

- An S corp must be a domestic business entity.

- All shareholders must be either U.S. citizens or legal residents of the United States.

- S corps can only offer one class of stock (common stock).

Moreover, some businesses are not allowed to become S corps including financial institutions, insurance companies, and domestic, international sales corporations. These restrictions, and the pass-through taxation aside, S corps function bureaucratically in much the same way as C corporations. They establish Articles of Corporation, hold annual meetings, and publish minutes. They must file annual reports and conduct other corporate formalities. Like traditional corporations, S corps have a “top-down” organizational structure in which a board of directors makes all critical decisions and elects officers to carry out the daily business of the company.

How does the S corp differ from other business and corporate structures?

S corporations were established to serve a specific historical and political purpose, the desire to incentivize small American businesses. By limiting the number of shareholders and stipulating that the company must be domestic, S corps are different from traditional C corps and LLCs, both of which can expand internationally and place no limit on the number of members. In addition to its structural limitations, S corps have the following features:

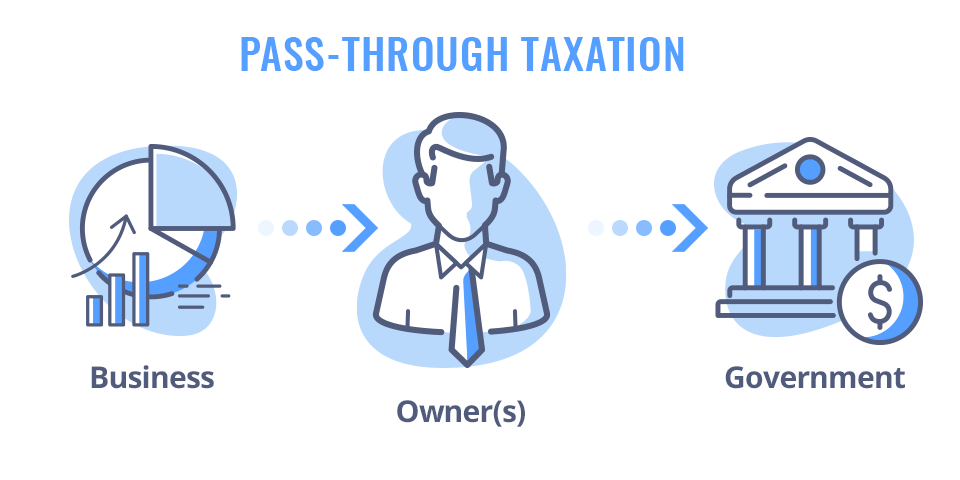

Pass-Through Taxation

In an S corp, profits from the business are divided among the shareholders, or investors, in the company. The shareholders then report the earnings as income on their individual 1040 form, and the IRS does not tax the business as a separate entity. In this way, S corps function like general partnerships, sole proprietorships, and LLCs. They are different from C corps, which are taxed first as an entity, and then later when shareholders receive distributions from the company in the form of stock.

Limited Liability Protection

Unlike sole proprietorships and general partnerships, S corps have limited liability protection. Should an individual, or an entity file suit against your company, they would not be able to come after your assets, in most cases.

Freely Transferable Stock

Although S corps only allow one class of stock, that stock can be sold or exchanged freely, meaning shareholders of an S corp can sell off a controlling interest in the company without obtaining the consent of other members. This practice is very different from how an LLC operates. An LLC’s operating agreement defines clear roles for all the members, including how much interest they have in the company and how they can divest of assets.

What are the advantages of becoming an S corp?

Asset Protection

Like LLCs and C corps, S corps have limited liability protection. Theoretically, that means that if the company gets sued, the claim cannot target your assets. Limited liability is a valuable feature, but many experts point out that it is not a silver bullet. For instance, if an S corp was initially an unincorporated partnership or sole proprietorship; an owner can still be liable for any claims or debts the company held before it incorporated. Likewise, an owner is responsible for any personal assets put up as collateral on a business loan. If the loan defaults, an S corp owner could lose the assets tied to the investment.

Tax Advantages

S corps are exempt from most federal income tax, except for some capital gains tax and taxation on personal income. Instead of being taxed as an entity, the way a C corp is, the S corp passes all income losses and gains through its shareholders. This structure effectively eliminates the double-taxation that results when a company pays its taxes, then the distributions to shareholders get taxed a second time. Another essential tax advantage comes from what might also be characterized as a strategic way of determining income. As a shareholder, you can be an owner of a business and pay yourself a salary, on which you would owe the necessary FICA taxes. You can also pay yourself in dividends; dividends are taxed at a much lower rate than your salary would be. The IRS is well-aware of the scope for abuse—i.e., some owners might want to pay themselves entirely in dividends to avoid paying their own FICA taxes—and requires S corp owners-employees to be paid a “reasonable salary.” Regardless, S corp owner-employees have a distinct advantage over the owners of unincorporated businesses. A sole proprietor must pay Social Security and Medicare taxes on all the businesses’ net earnings. Owner-employees of an S corp only pay taxes based on their compensation.

Easy Transfer of Ownership

Unlike an LLC, which determines ownership requirements and responsibilities through a founding document, ownership of an S corp is determined by who has a controlling share in the stock. The company cannot be liquidated if someone leaves, nor are there significant tax consequences or a need to comply with complex accounting rules. Likewise, the company has unlimited life; it does not cease to exist when the owner gets sick or dies.

What are the disadvantages of becoming an S corp?

While the S corp offers distinct tax advantages and ease of transferability, it is not the right choice for everyone. Here are some of the chief disadvantages of becoming an S corp:

Restrictions on Shareholders

The code establishes several limits on shareholders. There can only be 100, they all must be either American citizens or legal residents, and it cannot be an entity. That means you don’t have the option of raising venture capital or rapidly expanding the business by bringing in another company. Your primary source of raising money will be funneling profits back into the business.

Restrictions on the Class of Stock Offered

S corps can only issue common stock, which makes their company a less attractive option for investors who would rather have the benefit of receiving preferred stock.

Restrictions on Company Growth

S corps are an excellent choice for American companies that plan to offer American services and products indefinitely. For anyone who wants to work internationally or bring foreign members into the company, S corps are not a good option.

Red Tape, and Lots of It

Although S corps are allegedly triggered less for audits than unincorporated companies, you still need to do a lot of work to jump through the legal and tax loopholes that come with meeting the requirements of both, the corporate structure, and the IRS code regulations. There are state requirements on how to report minutes and shareholder records. The IRS is screening to make sure S corp owners don’t abuse their tax reporting. Anything less than due diligence, and you can lose your S corp status—possibly incurring a massive tax bill in the process.

Want to register your business as an S corp?

-

Choose a name.

It is essential to have a unique name, or you could face infringement issues later (you will also stand a better chance of getting the perfect domain name).

-

Get an Employer Identification Number.

You will need an employer identification number (EIN) , which is a nine-digit number the IRS assigns businesses operating in the United States. Use Filenow to apply for an EIN online today!

-

Choose a registered agent.

This is the person or entity, designated to receive all the corporation’s official correspondence. You should have the name of the registered agent chosen before you file the articles of incorporation because most states require you to submit the agent’s name and address along with the paperwork. Use Filenow’s registered agent services.

-

Register your small-business as a corporation in your state.

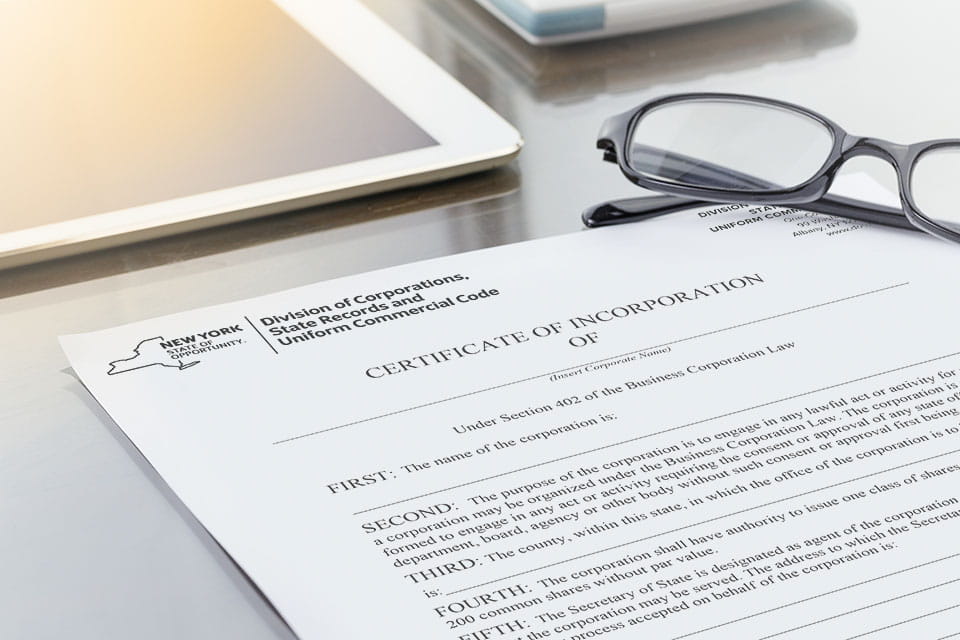

You must file Articles of Incorporation (sometimes called a Certificate of Incorporation) in the state where you plan to register the business. This comprehensive legal document outlines the essentials of your business and is required by every state. The most common information included in the Articles of Incorporation is the company name, its purpose, the board of directors, the officers, and the number of shares and their value. Every state requires you to file Articles of Incorporation, but each state has slightly different requirements, forms, and filing fees.

Example of New York State Certificate of Incorporation. -

Elect S corporation status.

The final step in the process of registering an S Corp is to notify the IRS—filing Articles of Incorporation with the state does not automatically confer your corporate tax status. To make it final, you must file Form 2553. If your business is newly incorporated, you must file the S Corp election within two months and 15 days of the date of formation for the election to take place in the first tax year.